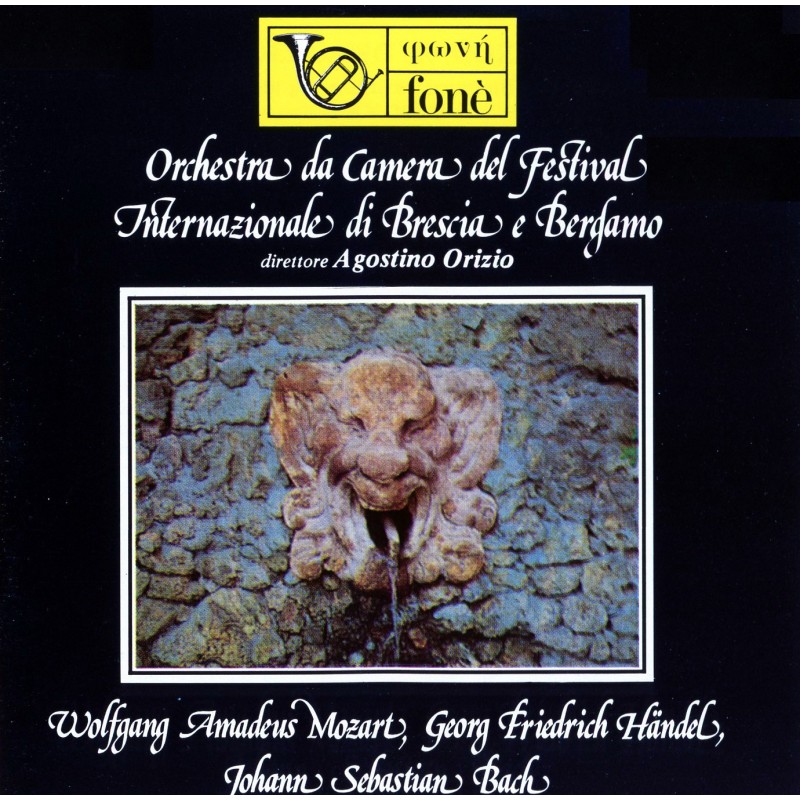

Orchestra da Camera del Festival Internazionale di Brescia e Bergamo - Mozart, Händel, Bach (High Resolution Audio)

Orchestra da Camera del Festival Internazionale di Brescia e Bergamo

Direttore Agostino Orizio

Wolfang Amadeus Mozart, Goerge Friedrich Händel, Johann Sebastina Bach

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART (1756 -1791)

Sinfonia concertante in mi bemolle maggiore per quattro strumenti a fiato e orchestra d’archi KV 297 b

Solisti: Rota, Vernizzi, Borgonovo, Mariotti

Allegro (14'05")

Adagio (8' 17")

Andantino (8'55")

GEORG FRIEDRICH HÄNDEL (1685-1759)

Concerto in re minore op. 7 n. 4 per organo e orchestra

Solista: Ernesto Merlini

Adagio (5'30")

Allegro (6'52") a (5 '05") Ad Libitum (Adagio: quasi una fantasia)

Allegro (4' 57")

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH (1685 -1750)

Concerto in re minore BWV 1060 per violino, oboe, archi e basso continuo

Solisti: Rizzi, Borgonovo

Allegro (4'57")

Adagio (5'25")

Allegro (4'02")

Durata: 1 h 03' 00"

Direttore di produzione Producer

Giulio Cesare Ricci

Direttore dell’incisione Recording Supervisor

Giulio Cesare Ricci

Ingegnere del suono Recording Engineer

Alessandro Orizio

Registrato nel mese di Maggio del 1987 presso il Teatro Grande in Brescia e la Basilica di Santa Maria delle Grazie in Brescia.

Microfoni utilizzati: Schoeps Colette C 41. Processore PCM: Sony PCM-F 1. Preamplificatore microfonico EMT. Vcr Betamax Sony SL F1E e SL HF100EC. Vcr U-Matic: Sony DRM 200. PCM: Sony 1630. Audio Editor: Sony 1100

WOLFGANG A. MOZART

Sinfonia concertante for wind instruments and orchestra KV 297 b

Allegro - Adagio – Andantino

Mozart wrote the splendid Sinfonia Concertante K V 297b in l 778, during a stay in Paris. for a “Concert Spirituel” and it is without doubt the less known and the least damaged by questionable interpretations of the Sinfonie Concertanti. At this time in Paris. (as, indeed in Italy), there was a certain leaning towards the baroque Concerto Grosso with its alternating “Concertino” and “Ripieno”. As a result. the socalled “Sinfonia Concertante”, with the interplay between soloists (always two or more in number) and orchestra which recalls baroque practice, enjoyed great popularity. Mozart himself wrote another wonderful “Sinfonia Concertante” for violin and viola, KV 364. The “gallante” spirit of the Mannheim school was still alive in Paris. and it was for four soloists from Mannheim that Mozart wrote the work heard on this recording, K V 297b. It was never actually performed for one of the “Concerts Spirituels” and the reason f or this remains one of the enigmas which surround many of Mozart’s works. The fate of the KV 297b is baffling: deemed to be a composition of fundamental importance by the best and most well respected wind ensembles over the course ·of time. not only was it not performed at the “Concerts Spirituels”, but the original manucript actually went missing under mysterious circumstances. First conceived to be performed by flute, oboe,bassoon and horn, the final version calls for a clarinet rather than a flute, and it bears traces of indiscreet tampering: nonetheless, it remains a work for instrumentation of the highest ski li and themusical content does not seem to have suffered significant damage. The opening Allegro is a marvellous introduction. In this movement. the solo group dominates, while the orchestra serves almost as an accompaniment. Above all the “cadenza” is remarkable, sustained in unison by the four instrumentalists who, through their virtuosity, reveal the true character of the work. But it is the sublime Adagio that offersthe soloists the possibility of demonstrating all of their ability and their skill.The Andantino, introduced by a quartet of wind instruments, and accompanied by a “Tutti”, in the style of a guitar, offers a theme which, through ten variations, leads to the finale. The whole of the third movement reflects the Parisian influence, be it the theme which, in its charm would seem to be part of an “opera-comique” or be it the Ritornello which is reminiscent of vadeville. Only the final variation, with its slower tempo becomes a solemn Adagio. The piece finishes, as was the custom, in a brilliant mood.As a combination, while the first and th1rd movements express all their delightful and eloquent vivacity, the Adagio remains one of the most sublime examples of spiritual uplifting. The care and wisdom with which Mozart employed each instrument of the orchestra in order to make maximum use of their various characteristics of timbre and colour is well-known. So, even when. as in this “Sinfonia Concertante”, the four soloists practically constitute a concertante group, the sonorous character of each single instrument remains marvellously individual.

GEORG FRIEDRICH HANDEL

Concerto in D minor, Op. 7 No. 4 f or organ and orchestra

Adagio - Allegro - Allegro

If Bach’s “interior” cosmopolitanism and Handel’s realistic, actual aperture on the world place the two greatest craftsmen of the late musical baroque on different levels, the German masters shared, during their lives, great fame as performers. For Bach, whose music was too often misunderstood in his lifetime, this fame was his only point of contact with what is commonly know as success; for Handel, it was one of the many facets of his offering to the European public as a versatile “personality” and fashionable artist. Georg Friedrich Handel must have been an extraordinary organist judging by the eye-witness accounts of Charles Burney and Sir John Hawkins, two famous figures of eighteenth century musical England and both friends of Handel who himself enjoyed renown and success in London. Particularly impressive to the listener was the German musician’s admirable gist for extemporization, both in the “solo” parts of a concerto and in the free improvisations. Even apart from the words of praise of Hawkins and Burney, we are left with the Concertos for organ and orchestra, about twenty in all, as testimony to an art which amazed Handel’s contemporaries. This musical form, concerto for organ and orchestra, was one which, with few exceptions, was born and subsequently died with Handel. The origin of these works, which Handel himself played between acts of his Oratorios, is particular, and we can therefore attribute them to the London period, that in which the German musician received, through these Oratorios. his fame as an operatic composer. Handel’s exceptional skill as an improvisor has already been mentioned, however, we must consider that, of the scores resulting from these concerts we have been left with only a fraction, albeit a significant une. of Handel’s organistic art. These scores provide skeletal frameworks for thewonderful free and imaginative unravelling or the improvisation which so enthralled the Oratorio -going public in London. Nevertheless, reading and listening to the scores reveals interesting details: in the first place, the improvisatory spirit is structurally fundamental to this music (the second movement of the Concerto Op. 7 No. 4. “Allegro”, is entirely “ad libiturm”); but above all, the brusque reversal or trends which, with the elegant and refined openmindedness of the up-to-date artist, Handel manages to impress upon the organ, and instrument which, since its origins, has been an ideal medium for the evocation of the mystic profundity of the liturgical service. However, through Handel, the instrument reaches a profanity which places it on the same plain as the brilliant and extrovert 18th century harpsichord. This is proof of the instrumental ambivalence of these compositions (intended “for the harpsichord and for the organ”; one of these concertos, Op. 4 No. 6, is also written for harp), which make powerful use of the agility of the harpsichord’s performing style, and which arrive at the general lack. with a few exceptions. of the obligato pedal. This was an omnipresent feature of the strict German organ tradition while English organs in Handel’s time were generally devoid of the pedal keyboard.

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

Concerto in D minor, BMW 1060, for violin, oboe, strings and bass continuo

Allegro - Adagio – Allegro

It is only recently that Bachian exegesis are arriving at conclusions which, while on one hand are shown to be nearer historical truth, on the other, cannot fail to provoke a certain sense of loss in those who may still be tied (and not always through their own limited point of view) to an impression of the Maestro of Eisenach handed down through the eighteen hundreds in Germany where romanticism was strongly influenced by a very Germanic mysticism and nationalism. This “new image”, as it is currently defined, has been strongly enforced by the late lamented Friedrich Blume and in recent years found a proud crusade in Piero Buscaroli. The latter has presented us with a more “tender” impression of Bach, sanguine and veracious which if not actually a thousand miles from the now “passé” portrait of the fervid craftsman of sound, wholly devoted to offering his wonderful “wares” “Soli Deo Gloria”, is nonetheless far-removed. Not only, therefore, was Bach a divine creator of sacred musical architecture, but a man complete his desire for a full life ever to the point of being mundane, almost courtly. Where the old image of Bach is perhaps the most sullied is in his post as “Cantor” at Leipsig: new research on the chronology of his work testifies not only that his ardent activity as a composer of sacred cantatas carne to an early end, but also that for many of these sacred works, the Passions included, Bach drew on elements from preceeding compositions. Besides his lack of patience for the terrible compositional routine to which, for reasons of his position, he was committed. Bach found stimulation enough in his direction. assumed in 1729, of the Collegium Musicum of Leipzig. one of the many musical consortiums which blossomed in Lutheran Europe, and which are still in existence today. There were associations of musicians, of the most capable instrumentalists, who performed for public concerts but also in caffe’s and in squares. The one in Leipzig prided itself on its noble tradition (it was founded by Telemann) and Bach was impassioned by his collaboration there to the point of dedicating to it a large part of his time, even detracting from his duties as “Cantor”. It was for this Collegium Musicum that Bach actively worked as a composer, bringing upon himself the fierce reprimands of his superiors at the Tomasschule for the scant way in which he carried out his duties: he worked readily for the Collegium, writing in part “ex novo”, and, above all, transcribing previous compositions for the available forces. This is the case of the Concerto BMV 1060: the version presented on this recording is a reconstruction of that which is currently retained to be the original version for violin, oboe, strings and bass continuo which was lost; we are left with only a version for two harpsichords, strings and bass continuo which Bach elaborated on for the accomplished harpsichord players of the Collegium Musicum, transposing the original key of D minor into C minor. We know nothing precise of the scoring of the original of which this performance by the Orchestra del Festival is a reconstruction, but if we accept in good faith, and there is no reason not to do so, the reconstruction of the version for violin and soloists, and if we suppose, as is plausible enough by virtue of noteable and consolidated practice, that the two right hands of the harpsichord players realized the monodiclines of the two original solo instruments, we cannot but marvel at Bach’s extraordinary capacity for adjusting to the practical necessities of changing instrumental forces within the same work, while, at the same time, enriching the music through wonderful technical solutions, both compositional and architectural.

Data sheet

-

Hd Tracks

Hd Tracks

- Visita il sito

-

High Res Audio

High Res Audio

- Visita il sito